Overview

This is a living document that will be revised periodically based on CanOSS community feedback and lessons learned.

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) refers to serious complications during pregnancy, labour, childbirth, or the postpartum period that result in severe illness, prolonged hospitalization, long-term disability, and high-case fatality.1,2 Severe maternal morbidity has been rising in Canada,3 contributing to increased rates of maternal mortality.4 Leading SMM conditions in Canada are severe pre-eclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver count, low platelets) syndrome, and severe postpartum hemorrhage.1 In addition to long-term health outcomes and risk of mortality, pregnant individuals may experience SMMs during subsequent pregnancies,2,5 and face adverse fetal outcomes.6

In response to a call from the World Health Organization in 2004 and 2015 to prioritize maternal health,7 SMM has become the most appropriate quality indicator of reproductive health care internationally.6 Consequently, many high-income countries (HICs) have focused their attention on reducing SMM, with variable approaches to monitoring and reviewing cases. Using different models, several HICs have developed nationwide Obstetric Surveillance Systems (OSS) to systematically identify contributing factors of SMM, as well as mortality, which then inform the development, implementation and evaluation of targeted recommendations aimed at reducing SMM.8–13 Canada does not have an OSS. Existing Canadian maternal surveillance systems and data repositories collect information on some demographic and clinical variables, however, these data do not capture contextual and process-related factors that contribute to SMM.2 Particularly, systemic factors that contribute to the quality of care provided to Indigenous, Black, gender diverse, 2SLGBTQA+, and racialized people are not often identified. This type of information is required in order to identify, and then make meaningful changes to processes that contribute to poor outcomes.

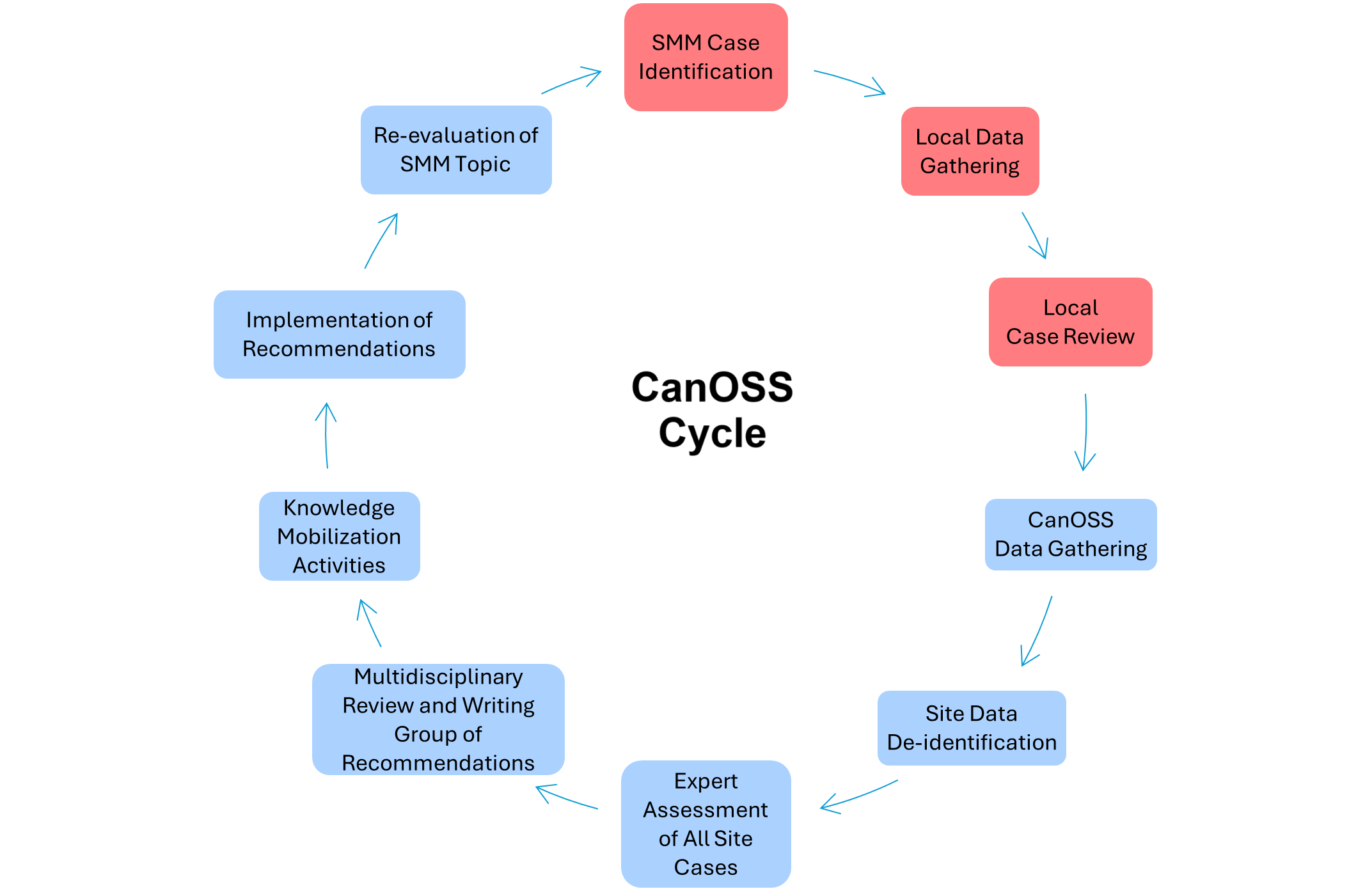

The Canadian Obstetric Survey System (CanOSS) is being designed in collaboration with clinicians and community members. To date, efforts have been made to determine its feasibility, with support from various grants.14–16 A national knowledge-creation Hub, that includes collaboration with persons with lived experience of SMM and members of marginalized communities, has also been developed to build knowledge mobilization tools, educational supports, and implementation strategies that will support CanOSS.17 Figure 1 illustrates the preliminary CanOSS process.

CanOSS-Ontario

Given Canada’s decentralized approach to healthcare delivery and data-sharing, and the diverse healthcare infrastructure between and within provinces and territories,18 there are several challenges to the development of a standardized survey system. Therefore, CanOSS will first be piloted in Ontario, which holds 38% of Canada’s population.19 Using feedback from key individuals involved in SMM case review, and informed by the preliminary CanOSS Cycle, existing systems for case review will be optimized and adapted to develop an effective CanOSS-Ontario process. CanOSS-Ontario will be a quality improvement (QI) project, similar to a public health program, that uses a systematic approach to review and evaluate SMM events that occur in Ontario. This system will help to identify opportunities to improve or change practice, and will provide a mechanism to implement such changes. All data entered into the CanOSS-system will be de-identified, and stored at McMaster University.

Figure 1. The CanOSS Cycle. Note: Red boxes indicate local processes. Blue boxes indicate CanOSS team processes.

References

- Dzakpasu S, Deb-Rinker P, Arbour L, Darling EK, Kramer MS, Liu S, et al. Severe maternal morbidity surveillance: Monitoring pregnant women at high risk for prolonged hospitalisation and death. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020; 34(4):427–39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31407359/

- Ukah UV, Platt RW, Auger N, Lisonkova S, Ray JG, Malhamé I, et al. Risk of recurrent severe maternal morbidity: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Nov;229(5):545.e1-545.e11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37301530/

- Dzakpasu S, Deb-Rinker P, Arbour L, Darling EK, Kramer MS, Liu S, et al. Severe Maternal Morbidity in Canada: Temporal Trends and Regional Variations, 2003-2016. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019 Nov;41(11):1589-1598.e16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31060985/

- Government of Canada. Statistics Canada. 2023. Fertlity indicators. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2022003-eng.htm

- Ray JG, Park AL, Dzakpasu S, Dayan N, Deb-Rinker P, Luo W, et al. Prevalence of Severe Maternal Morbidity and Factors Associated With Maternal Mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 9;1(7):e184571. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30646359/

- Geller SE, Koch AR, Garland CE, MacDonald EJ, Storey F, Lawton B. A global view of severe maternal morbidity: moving beyond maternal mortality. Reprod Health. 2018 Jun;15(S1):98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29945657/

- World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, UNDESA/Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366225/9789240068759-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Knight M, Lewis G, Acosta C, Kurinczuk J. Maternal near-miss case reviews: the UK approach. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121(s4):112–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.03.002

- Nair M, Choudhury MK, Choudhury SS, Kakoty SD, Sarma UC, Webster P, et al. IndOSS-Assam: investigating the feasibility of introducing a simple maternal morbidity surveillance and research system in Assam, India. BMJ Glob Health. 2016 Apr;1(1):e000024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28588919/

- Schaap TP, van den Akker T, Zwart JJ, van Roosmalen J, Bloemenkamp KWM. A national surveillance approach to monitor incidence of eclampsia: The Netherlands Obstetric Surveillance System. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(3):342–50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30346039/

- Donati S, Buoncristiano M, Lega I, D’Aloja P, Maraschini A, Group for the I working. The Italian Obstetric Surveillance System: Implementation of a bundle of population-based initiatives to reduce haemorrhagic maternal deaths. PLOS ONE. 2021 Apr 23;16(4):e0250373. https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/45616/ANN_19_04_10.pdf

- Tura AK, Girma S, Dessie Y, Bekele D, Stekelenburg J, Van Den Akker T, et al. Establishing the Ethiopian Obstetric Surveillance System for Monitoring Maternal Outcomes in Eastern Ethiopia: A Pilot Study. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2023 Apr 28;11(2):e2200281. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37116928/

- Qian J, Wolfson C, Neale D, Johnston CT, Atlas R, Sheffield JS, et al. Evaluating a pilot, facility-based severe maternal morbidity surveillance and review program in Maryland—an American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Rx at workT. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(4):1–4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36764455/

- Barrett J, D’Souza R. Launching the Canadian Obstetric Survey System – a pilot study. Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization (HAHSO) competition. Award period: 2 years. Award amount: $196,092.; 2023. Available from: https://ifpoc.org/project/launching-the-canadian-obstetric-survey-system-a-pilot-study/

- D’Souza R, Malhamé I. Improving Maternity Outcomes by Engaging Stakeholders in a Holistic Assessment of the Social and Clinical Determinants of Severe Maternal Morbidity in Canada – a Feasibility Study. CIHR Project Grant Competition. Award period: 3 years. Amount awarded $321,300. CIHR grant #462756.; 2021. Available from: https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/decisions/p/project_details.html?applId=444788&lang=en

- D’Souza R, Seymour RJ, Knight M, Dzakpasu S, Joseph KS, Thorne S, et al. Feasibility of establishing a Canadian Obstetric Survey System (CanOSS) for severe maternal morbidity: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2022 Mar 23;12(3):e061093. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35321901/

- Malhamé I, D’Souza R. Canadian Perinatal Programs Coalition. Co-creating knowledge mobilization activities to address pregnancy-related near-miss events and deaths in Canada. National Women’s Health Research Initiative: Pan-Canadian Women’s Health Coalition Hubs Competition. Award period: 4 years. Amount awarded: $439,106. CIHR grant #494770.; 2023. Available from: https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/decisions/p/project_details.html?applId=476802&lang=en

- CIHR Team on Improved Perinatal Health care Regionalization. Summary of Tiers of Obstetric and Neonatal Services in Canadian Hospitals. Vancouver; 2020. https://med-fom-phsr-obgyn.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2021/03/TOSDetailedJune2020.pdf

- Government of Canada SC. Population estimates, quarterly [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 11]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901